Ruins everywhere. There were no houses at all, only one wall of the Maharshal synagogue was left. I looked for where our house had been, where we lived. But there was nothing, rubble. And so I walked around. I cried.

–

Ewa Eisenkeit, born 1919 Lublin, recorded 2010.

Ruins of the Maharshal Synagogue on the site of the destroyed Jewish quarter in Podzamcze, Lublin after 1942.

Robert Rogowski’s Collection.

Lublin was liberated from German occupation on 22 July 1944. World War II ended in Berlin a year later on 8 May 1945. After the war, a physical, political, social and cultural border ran through Germany, dividing the continent into a democratic Western Europe and an Eastern Europe under Soviet control.

In June 1946, I returned to Lublin. I walked from the train station and didn’t see a single familiar face. I went first to the caretaker’s flat. He told me how everyone had died. My parents, my family and everyone else. The only consolation was that he gave me an envelope with a letter that said that my sister was alive, that she was in Otwock. The envelope also contained my school ID card, some photos of family, acquaintances, friends and myself. That was all I found. I know that my heart will never stop bleeding until the end of my life.

–

Symcha Wajs, born in 1911 in Piaski, recorded in 1999.

European Jewry was nearly wiped out – six million Jews had been murdered. The survivors could not and did not want to go back to their countries where their homes had been destroyed or taken over by locals and their communities lost. Postwar trauma and antisemitic violence in the decades after the war led many who had initially stayed to emigrate.

Empty space after the destruction of the Jewish quarter in Podzamcze, Lublin, 1948.

Stanisław Radzki’s Collection.

The destruction of Jewish heritage continued after the war. Synagogues, cemeteries and other signs of Jewish life fell into disrepair and the memory of the past was consigned to oblivion. Eastern Europe – once a vibrant centre of Jewish life – was now associated with mass murder and loss. A huge void existed in the middle of Europe, which is still seen and felt today.

Jewish cemetery in Frampol, 2019. In the foreground is the gravestone of Malka, daughter of Chajim Eliezer who died on 16 adar 1, 5622 (16th February 1862).

Author: Monika Tarajko.

In 1988, I decided that my sons should know what happened here. We went to Belzyce. I went to the mayor: ‘I’ve come with my sons to look for my father’s grave, where I buried him and I can’t find it.’ He said: ‘Come with me, I’ll show you.’ We went to this place where we hung around all the time. And what was there? It’s a place where young people are hanging out and there are trees. He tells me: ‘This was a Jewish cemetery.’ There are no gravestones here, there’s nothing here.

–

Nimrod Ariav, born in 1926 in Lublin, recorded in 2005.

Extras:

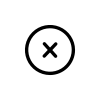

Ewa Eisenkeit

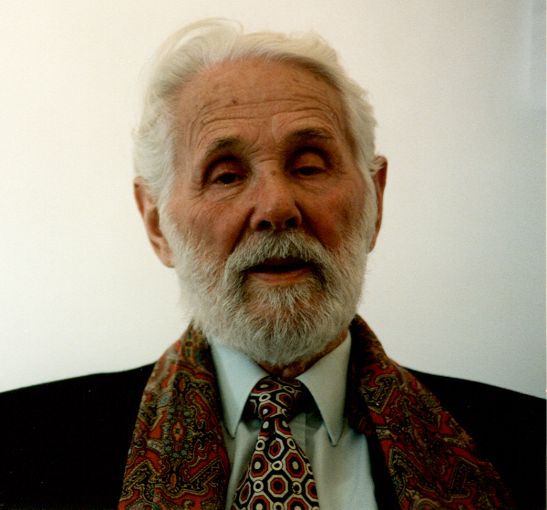

Symcha Binem Wajs

Nimrod Ariav

Stanisław Radzki’s Collection

Ewa Eisenkeit, née Szek, was born in Lublin in 1919 to Uszer Szek and Ester Bela Kerszenblat. Her paternal grandparents were Ibraham and Ester Bronia, while her maternal ones were Chana and Jakob Kerszenblat, who lived and ran a bakery in the Kalinowszczyzna district of Lublin. Ewa Eisenkeit had seven siblings. They were, in order of age, Sara, Ibraham, Cesia, Róźka, Jakob, Hanka and the youngest sister Basia. Ewa was the third child.

The Szeks lived lived at 40 Szeroka Street in Lublin. Ewa’s father ran a bakery and her mother was a homemaker. Before the war, Ewa attended the primary school at 18 Lubartowska Street, and then attended the Humanities Gimnazjum on Niecała Street, which she did not complete for financial reasons.

During WWII, the family, dealing in the bakery trade, continued baking bread, which was everybody’s staple food. In order to help support and feed her family, Ewa would leave the ghetto and wander around the villages outside Lublin, selling goods she had brought from the city and taking food back to the ghetto. She last left the ghetto on 14 March 1942, intending to take the rest of her family to the countryside. Two days later, the liquidation of the Podzamcze ghetto began. Ewa survived the war by wandering around the villages outside Lublin and getting help from people with whom she had previously traded.

She returned to Lublin after the liberation, initially living on relief provided by the Polish Red Cross. Of her large family consisting of her parents, seven siblings, grandparents and cousins, no one except for her survived the war. At the early postwar period, she supported herself by trading between Lublin and Łódź. She met her husband in the latter city and they left Poland in 1945, first for Berlin and then for France. They reached Israel in 1947 and moved to the US in 1961.

Ewa Eisenkeit had three children, a daughter and two sons. After her husband died, she took up a job in a laboratory.

Ewa Eisenkeit’s daughter, Esther Minars, published a book based on her memories, A Lublin Survivor: Life Is Like a Dream. Ewa Eisenkeit died in Lake Worth, Florida, in 2012.

Symcha Binem Wajs was born in Piaski on 24 April 1911 to Froim and Pesa Wajs. The family would spend most of the year at their country estate, located about 40 km outside Lublin, which was their main source of income. They would only come to Lublin for winter. When Symcha was a few years old, the family moved to Lublin for good, living at 23 Krakowskie Przedmieście.

Symcha attended a cheder on Kowalska Street, then a primary school and the Humanities Gimnazjum on Niecała Street. He obtained the qualifications of a dental technician before WWII. He was a member of the Young Communist League of Poland, for which he was arrested several times and searches were carried out at his home.

Just before the Germans entered Lublin, Symcha fled to the region of Volhynia, which was in the Soviet zone of occupied Poland. He met his future wife, Karolina, in Janowa Dolina in Volhynia. He worked as a dental technician. After Germany attacked the USSR in 1941, he and his wife evacuated to Kyrgyzstan. They returned to Poland with their two children in 1946. Of Symcha’s large family, only his sister, Anna Kubiak (born Chana Wajs), survived the war by living on “Aryan” papers in the Soviet Union.

In 1947, Symcha took part in a reunion of Lublin Holocaust survivors. He then moved to Warsaw and took up a job as an inspector of dental prosthetics at the Workers’ Treatment Centre. He completed a dental degree at Warsaw Medical Academy in 1958 and a PhD in 1965, following which he took up academic and didactic work, continuing it until retirement. From 1976 on, he was a senior assistant at the Department of Dental Prosthetics of the Institute of Dentistry at Warsaw Medical Academy. He edited the journals Protetyka Stomatologiczna and Archiwum Historii i Filozofii Medycyny. He published seven books and over 150 academic articles.

Symcha Wajs was active in protecting the heritage of Lublin Jews. He organised the celebrations of the 650th anniversary of Jewish presence in Lublin. He lobbied for the market square on Świętoduska Street to be named after the Ghetto Victims. It was also at his initiative that thirteen monuments and plaques were erected in Lublin to commemorate Lublin Jews, and the Lublin Jews Memorial Chamber was opened. He founded the Society for the Protection of Relics of Jewish Culture in Lublin in 1989, which he chaired until his death. The Polish Television made a film entitled W każdej garstce popiołu… (In Every Handful of Ashes…) in 1984, in which Symcha Wajs presented several fragments of the life and activity of Lublin Jews in the interwar period.

Symcha Wajs died on 9 September 1999 and was buried at the Okopowa Jewish Cemetery in Warsaw.

Nimrod Ariav (Szolem Cygielman) was born in Lublin on 24 September 1926 to Rajzla Matla (Marta), née Wajsbrodt, and Leib Cygielman. He had a twin brother, Abraham. He grew up in a flat at 17 Nowa Street in Lublin. His father’s family came from Lublin, and Nimrod’s grandfather Izrael Dawid lived at 8 Kowalska Street. His mother, who came from a wealthy family from Bełżyce, was involved in the Zionist movement and thus sent her two sons to the Tarbut Association school with Hebrew as the language of instruction. Afterwards, they both began their education at the Jewish Gymnasium at 3 Niecała Street in Lublin.

The family left for Bełżyce in 1940, where they stayed with relatives. Nimrod worked as a helper at the local power station. On 2 October 1942, his father, Leib Cygielman, was executed. Nimrod left for Warsaw at the end of 1942, where he began living on false “Aryan” papers under the name Henryk Górski. He began attending clandestine classes at the Śniadecki Secondary School. He joined the underground Home Army. In April 1943, he brought his brother Abraham to Warsaw. They moved into an apartment on Sienna Street together with a Jewish couple from Lublin, Jakub and Anna Rajs. Anna later became known as Anna Langfus. They were compromised a few months later and Abraham was killed during the arrest. Nimrod managed to escape. He changed his name to Jerzy Eugeniusz Godlewski and found another place to live. At the time, his mother was also hiding in Warsaw. Nimrod took part in the 1944 Warsaw Uprising, fighting on Sienna Street and in the Old Town, where he was seriously wounded and evacuated through the sewers. He was taken to hospital in Kraków after the uprising was lost, where he lived to see liberation in January 1945.

Nimrod briefly returned to Lublin in 1945 and then went to Łódź. At the end of 1945, he left Poland for Germany, where he began studying at the University of Munich. At the same time, he participated in organising the illegal transfer of Jews from Germany to Italy. He moved to France, where he became commander of a Haganah training camp. He left for Israel in 1948 and joined the military. He served in the air force and took part in Israel’s wars with the Arab states. He spent seven years in the military and left it with the rank of captain.

Nimrod worked for the Israel Aircraft Industries from 1954 to 1973 and later founded his own aviation company with branches all over the world: US, UK and Switzerland. He had two sons with his wife Odette, Abraham and Ariel. He regularly visited Bełżyce from 1987, where his efforts resulted in the successful restoration of the Jewish cemetery.

Nimrod Ariav died in Tel Aviv on 3 August 2023 at the age of 97.

Stanisław Radzki’s Collection

This collection of photographs from Barbara Radzka’s family archive presents a series of images of Lublin taken by her father-in-law, photographer Stanisław Radzki. The photographs document the streets of Lublin in the late 1940s and capture the wartime destruction of the city. The album contains valuable pictures of the site of the demolished Podzamcze Jewish quarter, then still not redeveloped, and images of the damaged historical monuments and streets of the Lublin city centre.

Stanisław Radzki’s Collection