Life was hard in the ghetto. We lived with 10 people in one big room with my mother’s family. We lived almost on the verge of starvation. In the beginning there were parts of the ghetto that were not fenced in and you could go out, although it was forbidden. But later they closed it and put Ukrainians or Latvians who collaborated with the Germans in charge, uniformed of course, and with weapons.The ghetto was fenced in with barbed wire, sometimes two-and-a-half metres or higher.

–

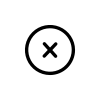

Aleksander Grinfeld, born 1922 Lublin, recorded 2006.

Szeroka Street, the main street of the Jewish quarter in Lublin, circa 1941.

Marek Gromaszek’s Collection.

On the order of Reinhard Heydrich, head of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA), concentration points for Jews were established in the occupied areas of Poland which became the ghettos. So-called Jewish councils were forced to administer these ghettos, which were misleadingly called ‘residential areas for Jews’ to create the illusion of self-determination. In reality, they were managed by the German administration.

‘Die evakuierten Juden werden zunächst Zug um Zug in sogenannte Durchgangsghettos verbracht, um von dort aus weiter nach dem Osten transportiert zu werden’.

‘The evacuated Jews will first be taken, group after group, to so-called transit ghettos from where they will be transported further to the East’.

Excerpt from the protocol of the Wannsee Conference, 20.01.1942, p. 8.

In March 1941, nearly 35,000 Lublin Jews were imprisoned in the ghetto; a third of the city’s population vanished from the streets. Over 400 ghettos in the General Government housed more than 1.5 million Jews; by 1942, there were nearly 450,000 Jews in the Warsaw ghetto.

Proclamation on the establishment of a closed Jewish residential district in Lublin, issued on 24.03.1941 by the Governor of the Lublin District Ernst Zörner. Source: State Archive in Lublin, ensemble no. 632, ref. 602.

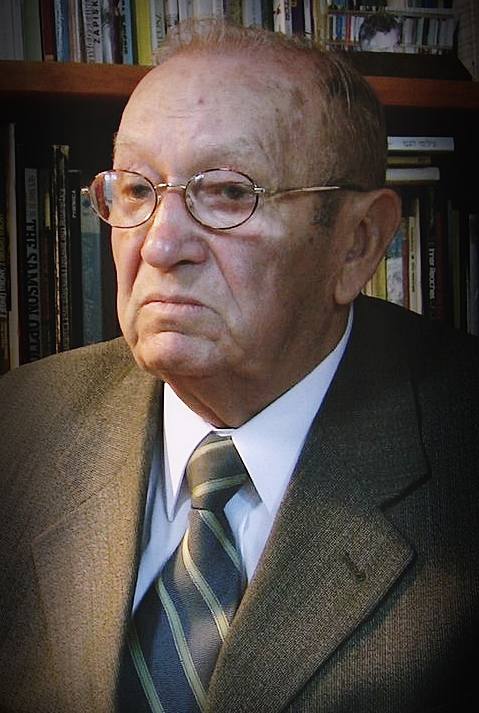

Inhabitants of the Lublin ghetto, circa 1941. Building behind the Grodzka Gate is seen in the background. Photo taken by a Wehrmacht soldier.

Andreas Rump’s Collection.

We, the children, were the providers in the ghetto. We took risks. When we saw that the guard had left, we crawled under the wires. We jumped outside the ghetto, bought food and brought it to our parents.

–

Morris Wajsbrot, born in 1930 in Lublin, recorded in 2010.

The living conditions in the ghettos varied and some were more isolated from the outside world than others, but they were all overcrowded. The residents died of starvation, disease and from the strain of forced labour.

In October 1941, a decree was passed imposing a death sentence on Jews who left the ghetto and on non-Jews who assisted them. Despite these harsh conditions, Jews managed to organise social, educational, political, and cultural programmes in the ghettos.

Ghetto fence in Podzamcze, Kowalska Street, 1942.

Source: National Museum in Lublin.

There were no ghettos in Germany or Western Europe, but Jews were forced to move into these specially designated houses.

A building at Lippehner Str. 35 in Berlin, which was used as a so-called ‘Jew house’ during the Second World War. Postcard, 1908.

Source: Simon Lütgemeyer.

Extras:

Aleksander Grinfeld

The Wannsee Conference Protocol

Morris Wajsbrot

Andres Rump’s Collection

Marek Gromaszek’s Collection

Aleksander Grinfeld was born in Lublin on 12 June 1922 to Wadia (Władysław) and Sura (Sala) Grinfeld. He had a younger brother Wiktor. His paternal grandparents were Chaim Zalman and Chaja Grinfeld, and his maternal ones were Israel Josef and Rywka Trachter. The family lived at 3 Krótka Street until 1940. Aleksander began his education at a primary school and was admitted to the Zamoyski Gimnazjum in 1934, where he studied until the outbreak of WWII.

The Grinfelds were moved to the Old Town during the war and lived initially in Aleksander’s grandmother’s house at 4 Rynek (Market Square) and later in the ghetto area, at 13 Grodzka Street, together with his mother’s family. Aleksander tried to work as much as possible so that he could have the opportunity to leave the ghetto. In 1940, he worked in a quarry near Świdnik, from where stone was sent for the construction of the airport. In the summer of the same year, he stayed in the village of Zadębie during the harvest. During the liquidation of the ghetto in April 1942, he decided to escape. He reached the Radom ghetto, where he spent almost two years working in a munitions factory, and in early March 1944, he was sent from there to Majdanek, where he worked sorting metal. He was transferred to the Plaszow camp a month and a half later, where he fell ill with typhus. He was then sent to the Wieliczka camp and then the Ebensee camp in Austria, where he was liberated by the Americans on 5 May 1945.

No one from Aleksander’s family survived. His father, a Judenrat official, was in the Lublin ghetto until the end. After its liquidation, he was sent to the Majdan Tatarski ghetto, and was most probably shot in the Krępiec forest. His younger brother managed to escape from the Lublin ghetto yet disappeared was not heard of again.

After the liberation, Alexander Grinfeld spent a few weeks in Austria, then made his way to Italy and to Palestine. He met his friend Sarah Zoberman in the early 1950s, whom he married in 1954. The Grinfelds live in Ramat Gan. They have one daughter and two grandsons.

The Wannsee Conference Protocol

The protocol of the meeting on 20 January 1942 starts with a list of the participants.

In general, the protocol’s language is deliberately designed to largely obscure the extent of injustice and violence. Mass killings planned and already carried out may well have been addressed, but any references to them in the protocol can only be found between the lines.

Section II describes the opening of the meeting. Reinhard Heydrich began by stating his remit and responsibility and the meeting’s aims. Then he continued with a report on the forced displacement of Jews so far. Section II of the protocol ends on page 5. It concludes by pointing out that the previous practice of emigration was now forbidden.

Section III opens by stating that the future approach will be the ‘evacuation of the Jews to the East’. It continues: ‘However, these operations should be regarded only as provisional options, though they are already supplying practical experience of vital importance in view of the coming «final solution of the Jewish question»’. Since the text here also mentions the ‘appropriate prior authorization by the Führer’, it contains a concrete reference to Hitler and his approval of these actions.

On page 7 at the bottom, the protocol deals with the plan of doing more than just exploiting the forced labour of Jews deported to the East: ‘In large labour columns, separated by sex, the Jews capable of working will be dispatched to these regions to build roads. In the process, a large portion will undoubtedly drop out through natural reduction’. In other words, the people were killed through forced labour.

Section IV (the last one) starts with page 10, documents the attempt to establish clear rules on which people should be deported. The protocol elaborates the various relationships in a family, including the so-called first- and second-degree Mischlinge – persons with Christian and Jewish parents or grandparents – as well as the question of ‘mixed marriages’.

There were 30 copies of the Wannsee protocol, but as yet only one single copy had been found. This original of the protocol is at the ‘Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amtes, Berlin’ (R 100857, Bl. 166–188).

Das Wannsee-Protokoll in der Originalfassung

The Wannsee-Protocol in English

Morris (Moses) Wajsbrot was born in Lublin on 1 January 1930 to Szoel Wajsbrot and Syrka, née also Wajsbrot. His siblings included the eldest brother Alte, then Lejb Symcha, Natan and the youngest sister Pola. The family lived in the Wieniawa district of Lublin, at 12 Długosza Street, and had grain stores in the backyard of the house, which was their family business.

In 1940, Morris was moved to the ghetto with his family and lived at 5, then 4 Kowalska Street. During the deportation of Jews from Lublin, his mother pushed him out of the train. He survived the occupation by wandering around villages outside Lublin, including Stawki and Płouszowice, and hiding in the fields and forests.

After the liberation, Morris and his brother ran a grain purchase business in Szewska Street in Lublin. He later worked as a taxi driver in Lublin for some ten to twelve years. Later, during the Gomułka government, he ran his own car parts shop, located on Bernardyńska Street. He was actively involved in the Lublin branches of the Congregation of the Mosaic Denomination in Lublin and the Social and Cultural Association of Jews in Poland (TSKŻ). He was one of the initiators of the erection of the Lublin Ghetto Victims monument in 1963.

After numerous persecutions and antisemitic attacks in 1968, Morris decided to leave Poland. With the help of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, he went to the United States via Denmark and Italy and settled in New York, where his older brother lived. Life in exile was hard at first. He worked at an electrical factory for a few years and later bought a supermarket with his partners. Finally, he opened a second grocery shop with his son-in-law, which he ran until his retirement.

Morris Wajsbrot was active on behalf of Lublin Jews in the United States and Poland. He was President of the New Lubliner & Vicinity Society for many years. Morris had two daughters and three grandchildren. He died in New York on 10 December 2010 at the age of 80.

Andres Rump’s Collection

On 17 September, the German troops approaching from the direction of Kraśnik stopped outside Lublin. Faced with heroic defence on the outskirts of the city, the Germans began shelling it with artillery fire and launched air raids, which completed the destruction wrought in the first days of the war. On the morning of 18 September, the German troops entered Lublin, and thus the five-year-long period of German occupation began for the city.

In August 2021, the ‘Grodzka Gate – NN Theatre’ Centre received wartime photographs donated by Andres Rump from Germany. The photographs come from the collection of his grandfather, who served in a Wehrmacht technical unit stationed at the Flugplatz on Wrońska Street in Lublin from 1941 to 1942.

Andres Rump’s Collection

Marek Gromaszek’s Collection

Wartime photographs of Lublin collection includes over 130 photographs from the private collection of Marek Gromaszek. Taken by German soldiers, they mainly depict images of the wartime districts of Podzamcze and the Old Town. Some feature information on the back and some are dated. Most are in a semi-postcard format. The entire collection has been digitised by the ‘Grodzka Gate – NN Theatre’ Centre.

Marek Gromaszek’s Collection