In the beginning, people didn’t usually tell. I didn’t even tell my children. When I was in Poland, my son said: ‘Well, now you can tell me’. So we sat together in the evenings and I told him. He says: ‘Mum, never in my life could I have thought that you lived through something like that’.

–

Regina Winograd, born in 1927 in Lublin, recorded in 2006.

The Mystery of Light and Darkness, carried out annually since 2002 by the ‘Grodzka Gate – NN Theatre’ Centre in Lublin. The event commemorates the beginning of the liquidation of the Lublin ghetto and the beginning of ‘Aktion Reinhardt’ on 16.03.1942.

Photo: Patryk Pawłowski, 16.03.2024.

The Jews who remained after the war tried to sustain the memory of the Holocaust. Evidence of the crimes and traces of Jewish life were collected. The first survivor testimonies were recorded as early as September 1944 in Lublin. From beneath the ruins of the Warsaw Ghetto, its archive, run by Emanuel Ringelbum’s group, was excavated.

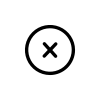

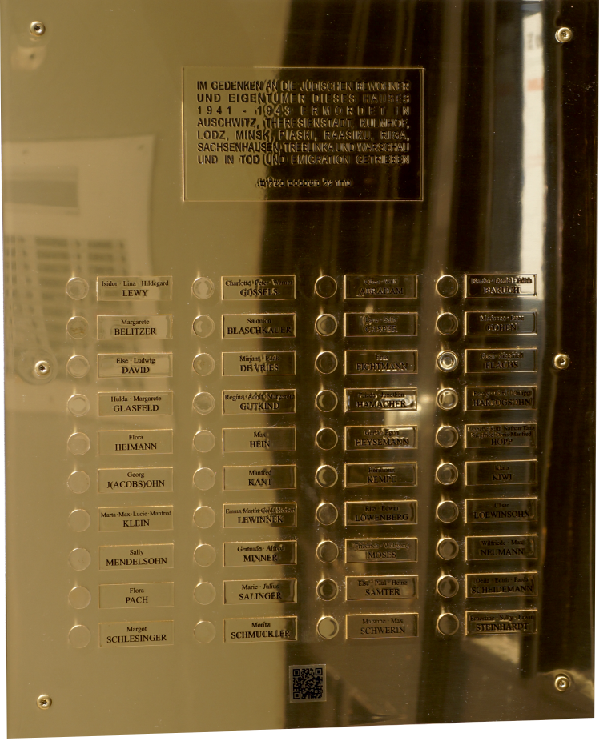

Memory Maps are hand-drawn maps of pre-war localities, recreated by their former inhabitants. They present a subjective image of the space, which changed irrevocably after the tragedy of World War II, losing its multicultural character.

Memory Map of Siedliszcze on the Wieprz River from 1925–1939, drawn by Tadeusz Mysłowski in 2005, based on the memories of Genowefa Hochman.

Source: The ‘Grodzka Gate – NN Theatre’ Centre in Lublin Archive.

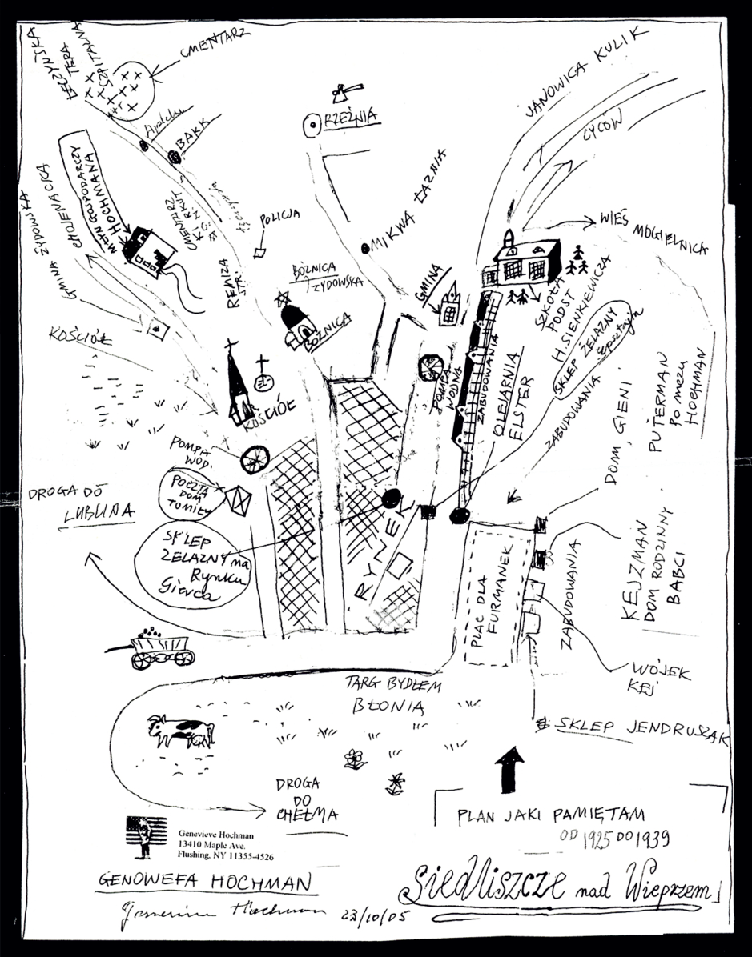

Over the years, in Poland and in divided Germany, official forms of Holocaust commemoration emerged, reflecting state narratives and the geopolitical situation. Institutions were established at historic sites; commemorative plaques and monuments were erected. Alongside official remembrance policy,

grassroots initiatives began to create their own forms of memorial culture. Such activities in both Poland and Germany have continued to confront local and national taboos up to the present.

Memorial plaque ‘Silent doorbell panel’ at a former ‘Jew house’ at Käthe Niederkirchner Str. 35 (formerly Lippehner Str. 35) in Berlin. The plaque shows the doorbell buttons and names of the former Jewish tenants.

Photo: Simon Lütgemeyer.

.

The Lamp of Memory at the site of the pre-war Jewish quarter in Lublin.

Photo: Joanna Zętar.

My family lies in Lublin in the ghetto, in Majdanek and in Bełżec, and in Łęczna near the synagogue. They lived there for hundreds of years, in Łęczna, in and around Lublin, and no one remains. How can you live with that?

–

Sabina Korn, born 1933 Łęczna, recorded 2006.

A part of the ‘Non/Memory of the Place’ art installation at the Umschlagplatz Memorial site in Lublin on Zimna Street. The art installation is a part of the Memory Trail ‘Lublin. Memory of the Holocaust’, created in 2017 by the ‘Grodzka Gate – NN Theatre’ Centre.

Photo: Tal Schwartz.

Materiały dodatkowe:

The Mystery of Light and Darkness

Regina Winograd

Sabina Korn

Maps of Memory

The Mystery of Light and Darkness

The primary way of commemorating March 16th is through the Mystery of Light and Darkness, held annually after dark at the Grodzka Gate. The ceremony begins with the reading of the names of the pre-war residents of the Jewish quarter, who were most likely deported in the first transport to the Belzec death camp.

Young people and teachers from Lublin’s schools, as well as local residents and anyone else willing to take part in the reading out of the names.

Subsequently, in the space where the Jewish quarter once stood, all lights are extinguished. Amidst the darkness, only a single lantern glows – the last surviving lamp from the Jewish quarter, symbolizing the Lamp of Memory. On the opposite side of the Gate, in the Old Town, lights remain on, and everyday life continues. The Grodzka Gate momentarily transforms itself into a gateway between Light and Darkness. Those participating in this commemoration move into the darkness, making their way toward the Lamp of Memory. It is at this site that we light a candle – the Light of Remembrance, which is then passed on from hand to hand by the participants, positioned along the road where Jews were led to the Umschlagplatz – the departure point for transports carrying Lublin Jews to the death camp.

The Mystery of Light and Darkness

Regina Winograd was born Rykla Milsztajn in Lublin on 8 October 1927 to Szlomo Milsztajn and Rywka, née Papier. She had five siblings: sisters Rachela and Ester, and brothers Eliezer, Josef and Uszer. She lived in Lublin at 65 Lubartowska Street (now 93 Lubartowska Street) until 1939. She attended the Jewish school on Lubartowska Street for a year and completed the next five classes at the public school in the Czwartek district of the city.

After the outbreak of WWII, Regina and her family fled to Rozkopaczew, where they hid with the Pył family, Polish peasants. Her father earned a living for the family by weaving, while her mother made medicines for the local population and livestock. The Winograds stayed in the village until the situation became dangerous due to Germans’ frequent visits, at which point they decided to separate. Regina Winograd and her sister Rachela first got to Lublin and then went to work in Germany.

After two years of hard work, Regina Winograd was liberated by the Americans and began to search for her family in the liberated Buchenwald concentration camp. She got to Switzerland with the help of the Red Cross, and in 1947 tried to go to Israel, ending up in Cyprus for two years, where she married a friend from pre-war Lublin and gave birth to a daughter. Having reached Israel, she provided psychological support and ran a ballet studio. She has a son and three grandchildren. She currently lives in Bat Yam. She has not found anyone from her family. She has visited Lublin several times and feels a strong connection to the city.

Sabina Korn was born Syma Najberg in Łęczna on 31 December 1933. She was the youngest child of Awraham Najberg and Fryda, née Rochman. She had three older brothers, Zalman, Israel and Leib. The family lived in Łęczna. Sabina’s mother ran the house, while her father, a Carpenter, worked at workshop in Warsaw that produced roof tiles and shingles. One of her brothers, Israel, died as a child shortly before the outbreak of WWII, and the Najbergs moved to Łochów near Treblinka, where Sabina started her primary school.

Following the creation of a ghetto for Jews from the Łochów area, the Najbergs had to move there. Sabina’s father was murdered by the Germans in the forest in 1941. Her mother, seeing no chance of survival in the ghetto, took the children and fled to the forest near Łochów. Sabina’s brothers hid for some time and were soon murdered by the Germans. Sabina and her mother wandered around the woods, hiding in haystacks, barns and holes dug in the ground. Her mother, looking for rescue, took Sabina to a family she knew in Łochów, who agreed to hide the girl, and this was the last time that she saw her mother. Sabina was taken to Warsaw and left in the care of Bronka Chmielińska, who, however, refused further help a few days later. It was the summer of 1943, and Sabina, then 10 years old, began wandering the streets of Warsaw. She was finally helped by Wanda and Alfred Rachalski, to whom she was taken just before the outbreak of the 1944 Warsaw Uprising. After the uprising was lost, she ended up in Milanówek under the care of Marta Orłowska and her daughter Halina, whom she helped with the housework, attended church and received Holy Communion.

In 1946, Sabina found her way to the Warsaw Jewish Committee, which collected surviving Jewish children. She first was taken to Bytom and then to Łódź. Then, with a group of other children, Sabina was sent to Palestine. She spent ten years in kibbutz Gan Shmuel and did her compulsory military service. She left the kibbutz in 1956. Her husband, also a Holocaust survivor, was from Ostrów Lubelski. She returned to Łęczna in the mid-1990s to search for information about her family. She has two sons and lives in Israel.

Maps of Memory

Maps of Memory are hand-drawn plans of pre-war towns and cities in Central and Eastern Europe, created by their former inhabitants (Jews and non-Jews), who thus sought to save from oblivion the shape and character of their towns and cities – destroyed or radically changed by the Second World War and post-war transformations.

Maps were often included in Memorial Books (Yizkor Book), published to commemorate specific Jewish communities that had been annihilated during the Holocaust. Sometimes the maps were accompanied by lists of names and even occupations carried out by the inhabitants.

These plans present varying levels of detail and aesthetics. They are usually based on the actual street network encompassing the centre of the village, but allow for freedom of perspective and proportion. The authors include private houses and public institutions that were important to the functioning of the entire community living there. Temples and cemeteries of various confessions are marked on each plan, reflecting the reality of life in a multicultural space inhabited by both Jewish and non-Jewish residents.

Piotr Nazaruk, The atlas of mental maps.