We always deluded ourselves that we were not being killed – we were being persecuted, but not killed. It seems to me that the whole story was actually that we did not believe until the last moment that we were all doomed to die. Maybe we did not want to believe.

–

Adam Adams, born in 1923 in Lublin, recorded in 2011.

The German invasion of the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941 led to an escalation of anti-Jewish policy. Behind the front lines, mobile killing units made up of police and SS shot nearly 2.2 million Jewish men, women and children.

The decision to murder all European Jews was made in late 1941, following several meetings between Hitler, Himmler, Heydrich and regional Nazi leaders (Gauleiter).

Page 6 of the protocol of the Wannsee Conference, 20.01.1942, listing the number of Jews in each area. The number of Jews in the General Government was estimated at 2,284,000.

The planning and construction of killing centres in Bełżec and Sobibór in the Lublin district and Treblinka in the Warsaw district began in the fall of 1941. Although these sites were close to railway lines, they remained isolated and hidden from the public. Lublin became the administrative headquarters of the ‘final solution’, managed by Odilo Globocnik, head of the SS and police in the Lublin district.

The headquarters of ‘Aktion Reinhardt’ in Lublin at 1 Spokojna Street, ca. 1941.

Marek Gromaszek’s Collection.

We knew there was going to be something, but it didn’t even cross anyone’s mind that such a thing could happen, that they would take us and kill everyone. They were killing people in their flats, those who couldn’t walk. And there were screams in the street too. It was so horrible. Then my sister was taken away. I can’t go on, I can’t talk about the liquidation anymore…

–

Judy Josephs, born in 1928 in Lublin, recorded in 2017.

The operation, called ‘Aktion Reinhardt’, started on 16 March 1942 with the first transports of Jews from Lublin and later from the Lwów ghetto to the Bełżec death camp. Nearly 28,000 Lublin Jews were murdered within a month. The area of the Jewish quarter in Lublin was destroyed and several thousand Jews were resettled to the Majdan Tatarski ghetto where they were used for forced labour.

Lublin Jews being deported to the Bełżec death camp, 1942.

Source: Yad Vashem Photo Archive.

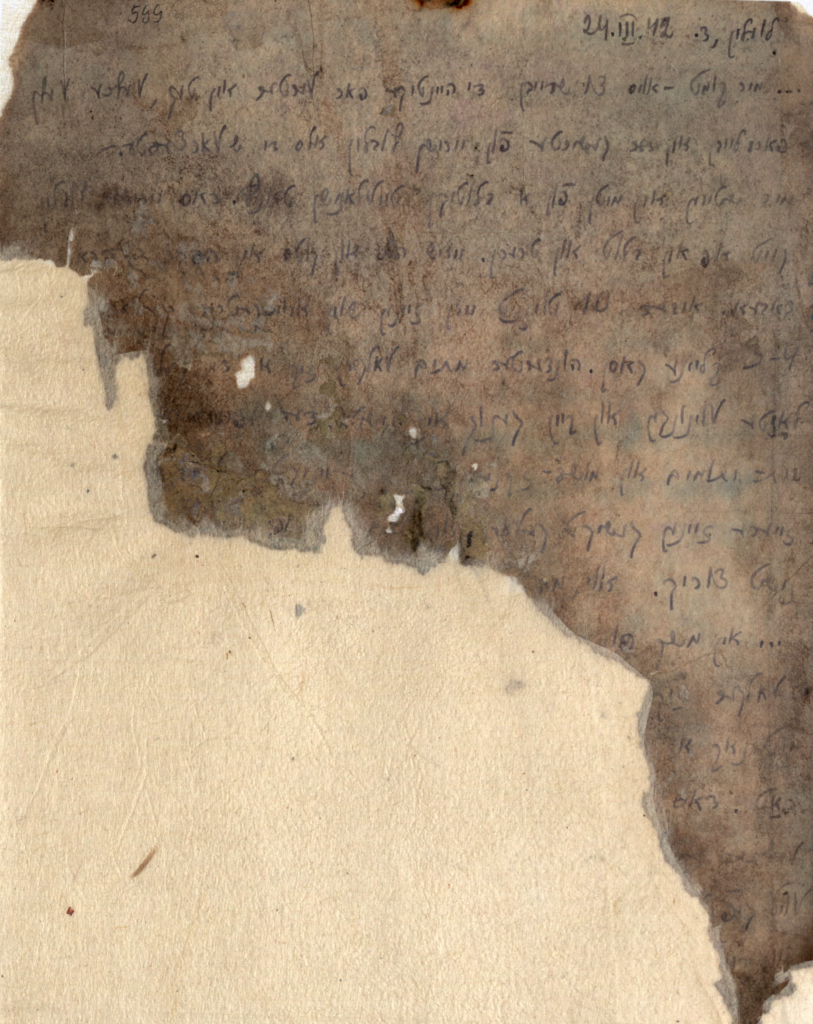

On 24 March 1942, someone who was in the Lublin ghetto during its liquidation, sent a letter describing these tragic events. We do not know the name or fate of its author, and the partially illegible text is the only evidence of his or her existence. The letter, written in Yiddish, have survived in the Ringelblum Archive:

The copy of the letter written by an unknown author in the Lublin ghetto, 24 March 1942, survived in the Ringelblum Archive in the Warsaw ghetto.

Source: Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw Archive.

[…] I had to add a few words today about days that will be remembered as the darkest in the history of Jewish Lublin. Jews are standing in the middle of a bloody devil’s dance. It […] Lublin, it is taking place in blood and tears. Jewish possessions without […]. Over 10,000 Jews already expelled […]. […] small streets. Hundreds of dead lay around […] abandoned apartments and without sufficient […] the orphanage and an old people’s home […] their […] were sent

[…] not back. And […] during […] we are wandering about mistreated […] tired, pained and broken. I can’t do more […] I can only shout to you: help. Add […] and the dead in shrouds. And […] go out […].–

NN

Materiały dodatkowe:

Adam Adams

Judy Josephs

The Wannsee Conference Protocol

Marek Gromaszek’s Collection

About the Ringelblum Archive

Adam Adams (Salek Mełamed) was born in Lublin on 1 April 1923. His father, Jakub Mełamed, came from Kowel. He ran a fabric warehouse, Manufaktura Lubelska (Lublin Manufacture), located at the corner of Lubartowska and Świętoduska Streets in Lublin. His mother, Mindla, née Cygielman, ran the house. Adam had three sisters: his older sister Andzia, whose married name was Zajwsztajn, Hela (Goldberg), and Róźka, a year and a half his junior. His maternal grandfather was a watchmaker and ran a shop on Krakowskie Przedmieście. Adam’s family lived in a house at 22 Narutowicza Street that his father co-owned.

Adam began his education at the Tarbut Hebrew School, where he completed seven grades. A Talmud teacher also came to their house to educate him. He then attended the Humanities Gimnazjum, but his education was interrupted by the outbreak of war.

Shortly after the Germans entered Lublin, Adam’s family was thrown out of their flat and moved into their father’s company. Some of the family tried to escape across the Bug River to the Soviet zone of occupation at the end of 1939, yet were caught and incarcerated in the Lublin Castle prison for several months. When in the ghetto, they lived on Lubartowska Street, then were resettled to the Majdan Tatarski ghetto. He and his father escaped to Warsaw, where they stayed in the small ghetto for several months until it was liquidated, following which they escaped back to Lublin to the Majdan Tatarski ghetto. Adam decided to flee with his friend Julek Fogelgarn and found their way to an acquaintance, Justyna Cękalska, living on Środkowa Street, who hid them in her cellar. They spent over six months there until Lublin was liberated. Justyna Cękalska was awarded the medal Righteous Among the Nations after the war.

Adam joined the Polish military after the liberation in 1944. He was demobilised in 1945 and left for Wałbrzych, where he ran a grocery shop for a short time. He met Alicja who came from Drohobycz and married her in 1946. They soon left for Paris and two years later for London, where they settled for good. They had one son. Adam ran a tie factory in England and retired in 1992, passing the business on to his son. He died in 2020.

Judy Josephs was born Jochweta Finkelsztein in Lublin on 15 August 1928 to Chuna Finkelsztein and Rachela, née Grinberg. Her father had a tailor shop, which was located on Narutowicza Street, while her mother ran the house. She had one sister, Brandla, and three brothers, Izaak, Eli and Mosze. The family lived at 12 Misjonarska Street in Lublin.

During the German occupation, Judy and her family were moved to the Lublin ghetto. She managed to escape through the barbed wire during the liquidation of the ghetto and make her way to Osmolice. Her parents joined her later. The family stayed in Osmolice from March to October 1942, when Judy’s parents were deported to Bełżec. Judy, at her brother’s insistence, volunteered as a non-Jewish Pole to go to work in Germany. She worked at an architect’s office and then as a maid at the chief architect’s house. Fearing her true identity would be recognised, Judy decided to flee Berlin a few months later. She made her way to the General Government and hid on “Aryan papers” in Rogów until the end of the war, working as a maid with a Polish family.

After liberation, Judy returned to her flat on Misjonarska Street. She had lost her entire family during the war, and seeing no prospects for herself, she and her cousin made their way to the American zone of occupied Germany and then further to Palestine. She started a family, has children and grandchildren. She lives in the United States.

The Wannsee Conference Protocol

The protocol of the meeting on 20 January 1942 starts with a list of the participants.In general, the protocol’s language is deliberately designed to largely obscure the extent of injustice and violence. Mass killings planned and already carried out may well have been addressed, but any references to them in the protocol can only be found between the lines.

Section II describes the opening of the meeting. Reinhard Heydrich began by stating his remit and responsibility and the meeting’s aims. Then he continued with a report on the forced displacement of Jews so far. Section II of the protocol ends on page 5. It concludes by pointing out that the previous practice of emigration was now forbidden.

Section III opens by stating that the future approach will be the ‘evacuation of the Jews to the East’. It continues: ‘However, these operations should be regarded only as provisional options, though they are already supplying practical experience of vital importance in view of the coming «final solution of the Jewish question»’. Since the text here also mentions the ‘appropriate prior authorization by the Führer’, it contains a concrete reference to Hitler and his approval of these actions.

On page 7 at the bottom, the protocol deals with the plan of doing more than just exploiting the forced labour of Jews deported to the East: ‘In large labour columns, separated by sex, the Jews capable of working will be dispatched to these regions to build roads. In the process, a large portion will undoubtedly drop out through natural reduction’. In other words, the people were killed through forced labour.

Das Wannsee-Protokoll in der Originalfassung

The Wannsee-Protocol in English

Marek Gromaszek’s Collection

Wartime photographs of Lublin collection includes over 130 photographs from the private collection of Marek Gromaszek. Taken by German soldiers, they mainly depict images of the wartime districts of Podzamcze and the Old Town. Some feature information on the back and some are dated. Most are in a semi-postcard format. The entire collection has been digitised by the ‘Grodzka Gate – NN Theatre’ Centre.

Marek Gromaszek’s Collection

About the Ringelblum Archive

The Underground Archive of the Warsaw Ghetto, known as the Ringelblum Archive, has been inscribed on the UNESCO Memory of the World List as a World Heritage Site. It is a unique collection of documents, one of the most important testimonies to the life and extermination of Polish Jews.

In November 1940, on the initiative of the historian Dr Emanuel Ringelblum, the Oneg Szabat (Joy of Saturday) organisation, which he founded in the Warsaw Ghetto, began to collect and compile documentation on the fate of Jews under German occupation. Emanuel Ringelblum and most of his fellow workers did not live to see the end of the war. The surviving archive contains over 35,000 documents and is kept at the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw.

Jewish Historical Institute

Book series Ringelblum Archive