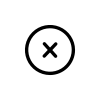

Painting by Wacław Kołodziejczyk entitled ‘General view of the death camp in Bełżec’.

Property: St. Mary Queen of Poland Parish in Bełżec.

On 28 April 1943, the last Jews were driven out of Izbica and taken to Sobibór. My parents were taken to the gas chamber there and I was taken to work. There was only a selection where they needed people to work. I was in Sobibór for six months, until the uprising. On 14 October, in almost one hour we killed all the Germans with knives, axes, took their weapons and set off the uprising. After the uprising we escaped and hid in the forest.

–

Tomasz Tojvi Blatt, born in 1927 in Izbica, recorded in 2004.

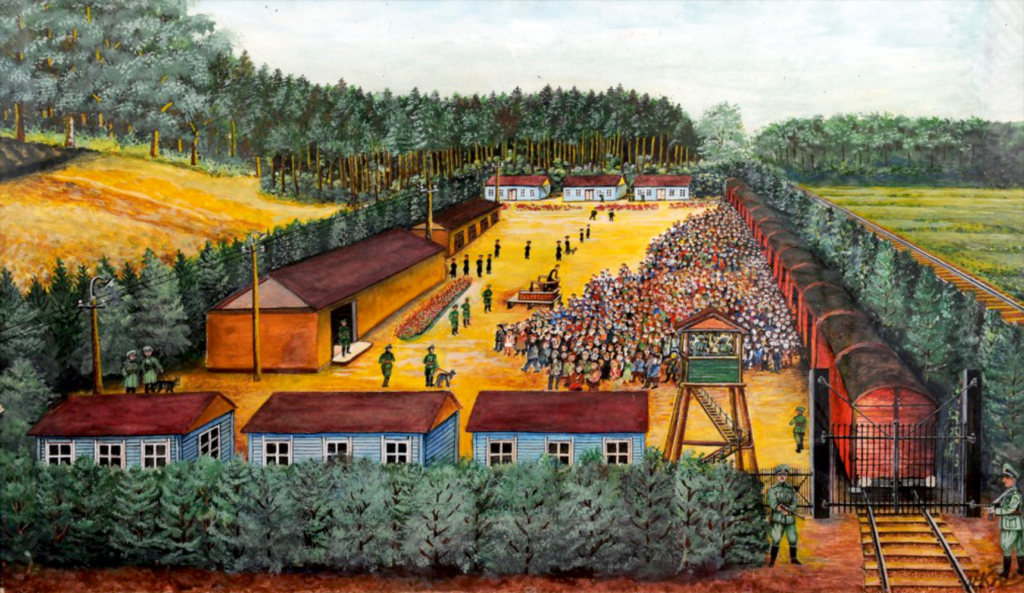

‘Aktion Reinhardt’ was named for Reinhard Heydrich after his death. Globocnik’s staff consisted of German and Austrian men who had been the main perpetrators of ‘Aktion T4’ – the operation to murder people with disabilities. The auxiliary staff was made up of Soviet prisoners of war who had been forcefully recruited. Although only a few hundred men served in the ‘Aktion Reinhardt’ death camps, they succeeded in implementing industrialised killing methods that proved very effective.

SS guards in Bełżec death camp in 1942. From left to right: Fritz Tauscher, Karl Schluch, Reinhold Feix, NN, Karl Gringer, Ernst Zierke, Lorenz Hackenholt Arthur Dachsel and Heinrich Barbel.

Source: USHMM, Washington, DC.

By late 1942 Bełżec was no longer in operation. The killing continued in Sobibór and Treblinka until the summer and fall of 1943. The camps were closed following uprisings and prisoner escapes and the Germans razed the sites to the ground.

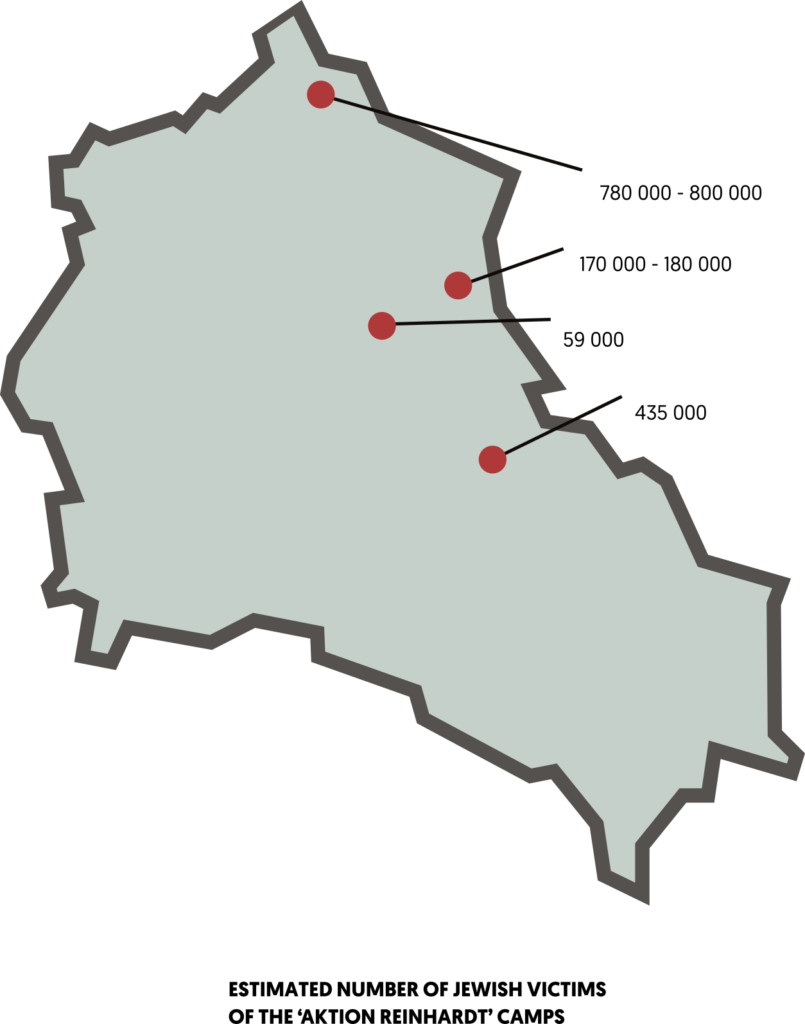

In July 1942, my father and I found ourselves in Belzec near the railway station, by the fertiliser warehouse. We were on a horse cart. Soon a freight train of cattle wagons pulled up in front of the warehouse. Slowly it rolled onto the tracks. I do not know what to compare this train to. When it stopped, it trembled on the rails. It seemed as if it would jump off them. The windows were full of human hands. White smoke from unquenched lime was billowing. We heard shouts of: ‘Water, water!’ They were shouting in Polish, they were Polish Jews. From the guard booths, guards jumped down to the ground, in helmets, with bayonets on their rifles, and took up their posts by the wagons. They walked back and forth. Every few minutes the steam engine would push this terrible transport forward, towards the camp. There I was able to count the wagons – there were 26 of them.

–

Jan Dzikowski, born 1926 Dzierzkowice, recorded 2007.

Memory map of the railway ramp at the Belzec death camp in 1942, drawn in 2007 by Jan Dzikowski who witnessed the deportation train’s arrival at the camp.

When we left Belzec, the lights were already on in the lanterns around the camp. There was a very intense smell of pine trees. Suddenly there was a strong scream, it was difficult to determine what it was, a scream

or something animal bursting into the sky. And there was a series of one, two, a few isolated rifle shots. We rode slowly, as if we had been flogged. And the horses sensed that something was wrong because they went leg after leg. My father was a tough guy, but he couldn’t pull himself together for a week, not

to work or do anything, so strong was the shock he experienced. After all, so many thousands of people had died in the blink of an eye… The smell of pine on the hill is deeply engraved in my memory… A smell,

but a bad memory.–

Jan Dzikowski, born 1926 Dzierzkowice, recorded 2007.

The last major operation, called ‘Aktion Erntefest’, took place on 3–4 November 1943, during which more than 42,000 Jews in the Majdanek camp and in the Poniatowa and Trawniki labour camps were executed. The Nazi territories were declared ‘free of Jews’.

More than 1.8 million Jews and an unknown number of Sinti and Roma were killed in ‘Aktion Reinhardt’.

Extras:

Tomasz Blatt

Jan Dzikowski

Paintings by Wacław Kołodziejczyk

Tomasz (Thomas) Blatt (Toivi Blatt) was born in Izbica on 15 April 1927 to Leon Blatt, a former soldier of the Polish Legions during WWI who ran a liquor shop, and Fajga, who ran the house. He had a brother, Hersz, six years his junior. Tomasz went to primary school in Izbica and attended a cheder in the afternoon, where he learned prayers and Hebrew.

In 1941, the Germans created an open ghetto in Izbica. The Blatts lived together until 1942. At the end of 1942, Tomasz obtained false documents and tried to escape to Hungary, yet was caught and imprisoned. He returned to Izbica in April 1943 and found his family among the handful of surviving Jews working in the local tannery. On 28 April 1943, Tomasz was deported to the Sobibor death camp with his family. His parents and younger brother were murdered in the gas chamber. He was selected for work and was employed, among other things, in the camp workshop. He took part in an uprising in the camp on 14 October 1943 and managed to escape with a group of about 300 people, of whom only one in ten survived until the end of the war. He hid with several other Jews at a farmer’s home near Izbica. All those hiding except for Tomasz were shot. Blatt, wounded in the jaw, managed to escape and continued to hide in Ostrzyca and Mchy, villages near Izbica, where he survived until the end of the war.

After the liberation in the summer of 1944, Tomasz went to Lublin and lived at 4 Kowalska Street. He found temporary employment at a locksmith’s workshop. He served briefly in the Polish People’s Army, and took part in a training course at the Officers’ Political School in Łódź. He worked as a desk officer at the Puck post of the Public Security Office in Wejherowo from the summer of 1948, yet was dismissed from service on disciplinary grounds in the autumn of 1949.

Tomasz emigrated to Israel in 1957 and settled in the US a year later. He became involved in documenting the Holocaust. He recorded an interview with Alexander “Sasha” Pechersky, one of the leaders of the Sobibor uprising, in 1979, and with Karl Frenzel, a former SS officer from Sobibor, in 1983. The transcript of the latter interview was published in the German, Polish and Israeli press. Tomasz testified as a witness at the trials of Nazi criminals. He published his memoirs: From the Ashes of Sobibor: A story of survival (1997), Sobibor: The Forgotten Revolt (1997), Escape from Sobibor (2010). His memoirs were the basis for the film Escape from Sobibor (1987), which received two Golden Globe Awards and several Emmy Award nominations. Tomasz Blatt is the protagonist of Hanna Krall’s story “Portrait with a Bullet in the Jaw”.

He lived in Santa Barbara, California. He was awarded the Officer’s Cross of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland on the 70th anniversary of the Sobibor camp uprising for his bravery and heroism during the revolt and for his outstanding contribution to the preservation of the memory of the Holocaust. He had three children, Hanna, Rena and Leonard, six grandchildren and four great-grandchildren. Thomas Blatt died in Santa Barbara, California, on 31 October 2015 at the age of 88.

Jan Dzikowski was born in Dzierzkowice on 1 June 1926. His parents worked the land. He had no siblings. In 1928, the family moved to the vicinity of Bełżec, settling in Korhynie near Jarczów, where they spent the time of the German occupation. He started his education in the two-grade village primary school, where he went to for three years, and then continued in the seven-grade school in Jarczów.

In 1941, a Jewish family – Dawid Nuchim with his wife and two sons – lived at Jan’s family’s house for the entire summer. They stayed with them until the so-caled “final settlement of the Jewish question”, when, in accordance with a German order, they reported for deportation to Bełżec.

In 1944, Jan Dzikowski returned with his parents to Dzierzkowice, where he began to learn tailoring, and after completing his military service in 1952, he began working as a tailor. He worked in the trade for 37 years, specialising in making men’s suits. He has a wife and two sons. He lives in Kraśnik.

Painting by Waclaw Kołodziejczyk

During the Second World War, Wacław Kołodziejczyk worked at the railway station in Belzec. In the 1960s, he created a series of paintings depicting the Bełżec extermination camp during the German occupation.

He witnessed Jews being transported to the camp, but he had never been to the camp himself. For this reason, his paintings should be understood as an artistic interpretation.

Painting by Waclaw Kołodziejczyk entitled. ‘General view of the death camp in Belzec’. The painting was provided with a description: A fragment of the unloading of people from the wagons destined for death. The camp was in operation from the month of March 1942 to the spring of 1943. During this time, approximately one million eight hundred thousand people were brought in and killed in a special gas chamber. A Jew called Irmann, who led 23 people from his immediate family, including his fiancée, into the gas chamber. And he always spoke briefly: ‘Ihr gehts jetzt baden, nachher werdet ihr zur Arbeit geschickt’ (Now there will be a bath, and then you will be assigned to work).

Property: St. Mary Queen of Poland Parish in Bełżec.

Painting by Wacław Kołodziejczyk entitled: ‘The area of the death camp in Belzec. A view at night’. The painting was provided with a description: ‘The burning of human victims after a previous murder by gassing. The burning lasted from the month of April 1943 to the month of February 1944. The area was then flattened and wooded’.

Property: St. Mary Queen of Poland Parish in Bełżec.

Painting by Wacław Kołodziejczyk entitled: ‘The building of the railway station in Belzec’. The station in Belzec was bombed by Soviet air forces on 5 July 1944.

Property: St. Mary Queen of Poland Parish in Bełżec.