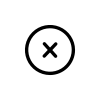

‘Aktion Reinhardt’ is a crucial but little-known chapter of the Holocaust. It was part of the Nazi plan to murder the European Jews, seize their property and acquire space ‘in the East’ for German settlements. After Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, millions of Polish citizens became victims of a ruthless occupation. From the start, the Nazi persecution of Jews was a central policy driven by racial antisemitism.

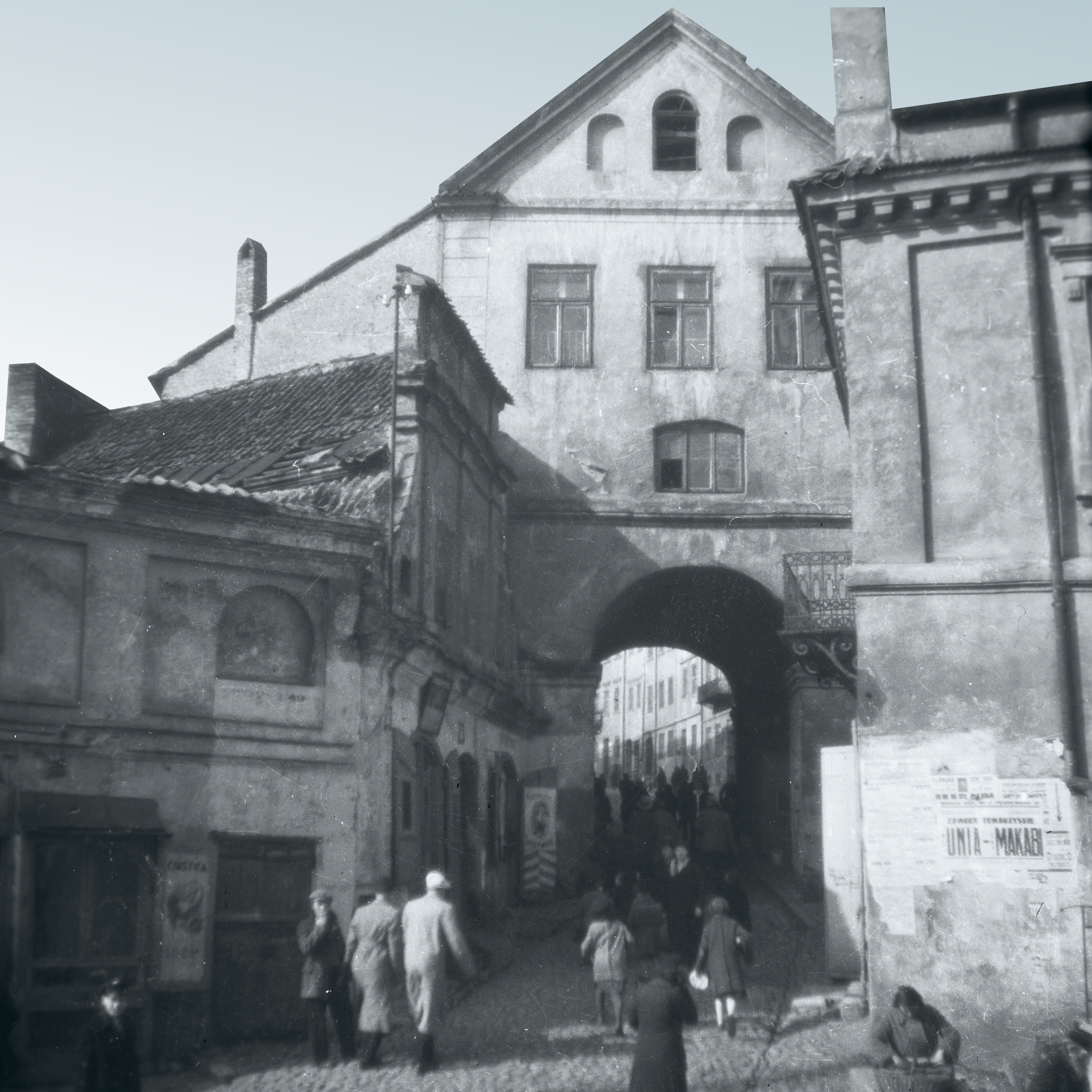

Ruins of the Jewish quarter in Podzamcze, Lublin, destroyed by the Germans after the liquidation of the ghetto in 1942. The Maharshal Synagogue is seen in the background.

Symcha Wajs’s Collection.

When I was making my family tree, I counted how many people had died during the Holocaust in Poland. Thirty eight! It was traumatic. They died because they were Jews. For me, that is the Holocaust. For me it is so horrible because I don’t know where they died. It is not a statistic for me.–

Sara Barnea, born in 1930 in Tomaszów Lubelski, recorded in 2006.

The Holocaust was centrally coordinated at the Wannsee Conference in Berlin on 20 January 1942. Fifteen men met to discuss the fate of millions and plan their deportation and mass murder throughout Europe. ‘Aktion Reinhardt’ began 8 weeks later with the deportations from the Lublin ghetto on 16 March. Deportations from many other places followed in the days and weeks after.

‘Im Zuge der praktischen Durchführung der Endlösung wird Europa vom Westen nach Osten durchgekämmt’.

‘In the course of the practical implementation of the final solution, Europe will be combed through from West to East’.

Excerpt from the protocol of the Wannsee Conference, 20.01.1942, p. 8.

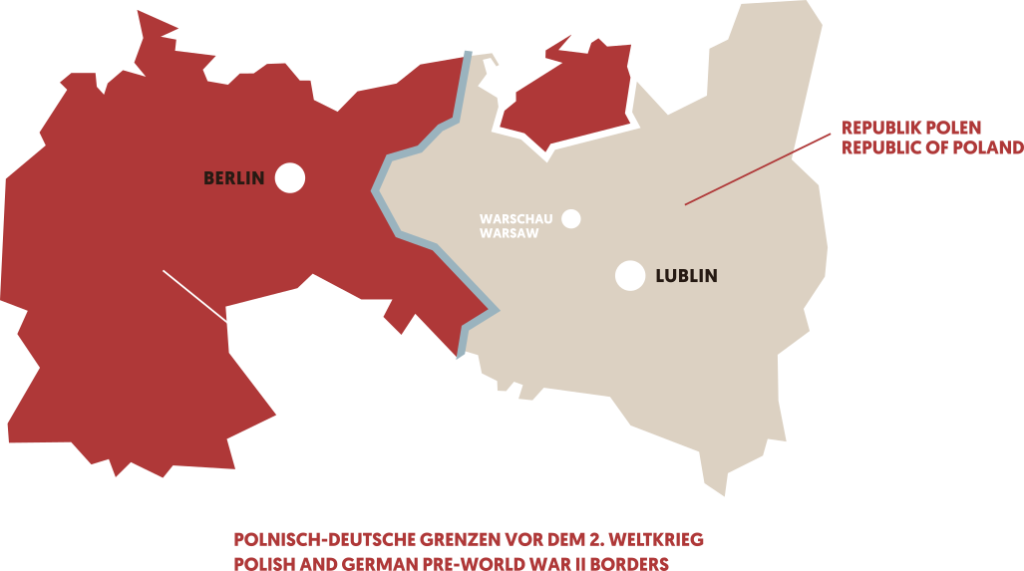

Villa on Lake Wannsee in Berlin, where fifteen high-ranking Nazis met on 20.1.1942 to discuss their cooperation in the planned deportation and extermination of European Jews. The villa is now the House of the Wannsee Conference Memorial and Educational Site.

By November 1943, over 1.8 million Jews from across Europe had been murdered in the death camps of Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka and Majdanek. Most of the victims have never been identified. These lost communities and their culture have left behind a void that continues to be felt today.

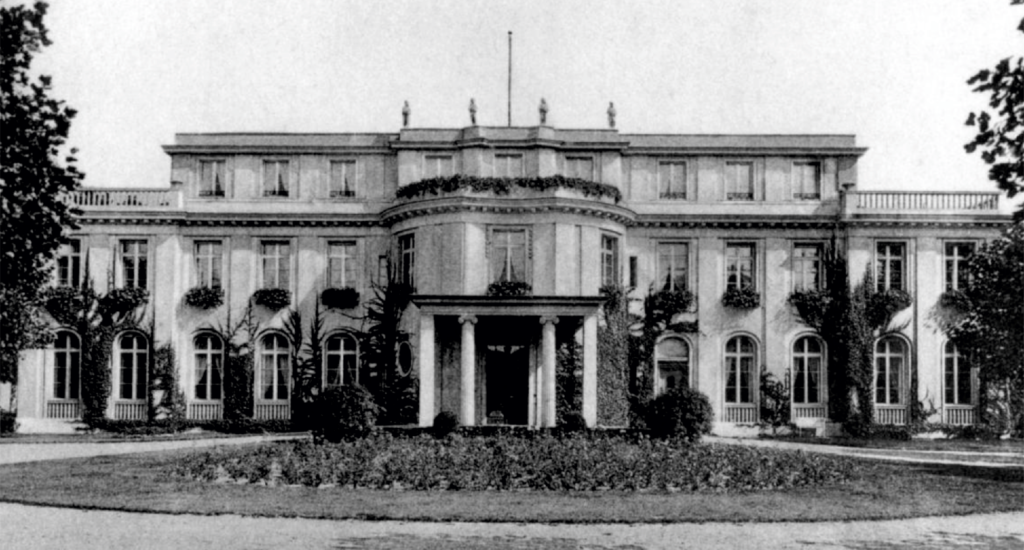

Grodzka Gate in Lublin, 1931, view from the Jewish quarter in Podzamcze. It currently houses the ‘Grodzka Gate – NN Theatre’ Centre which preserves the memory of the Lublin Jews.

Photo: Edward Hartwig. Ewa Hartwig-Fijałkowska’s Collection.

Extras:

Sara Barnea

The Wannsee Conference Protocol

The Wannsee Conference

Ewa Hartwig-Fijałkowska’s Collection

Symcha Wajs’s Collection

Sara Barnea, née Frydman, was born in Tomaszów Lubelski on 10 December 1930 to Szmuel Frydman and Mirla Gorzyczańska. Her paternal grandparents, Mala and Efraim Frydman, lived in Lublin at 35 Lubartowska Street. Her maternal grandparents Fiszel and Mindla Gorzyczański, lived in Tomaszów, where her grandfather ran a wine and vodka store.

Sara’s parents left for Lublin following her older brother’s death. She grew up with her grandparents in Tomaszów and was taken back by her parents only some time later. They lived in the Lublin Old Town, in the fifth house on the left behind the Krakowska Gate. She attended a cheder and the Bet Yakov Jewish school for girls on Lubartowska Street in Lublin, and later a Polish primary school in Tomaszów.

When WWII broke out, Sara was in Tomaszów, from which she fled with her parents to the Soviet territories of occupied Poland and was deported deep into the USSR, where she survived the war. After returning from the USSR, she ended up in Szczecin, where she studied at a gimnazjum (or junior high school) and a liceum (or high school) for adults, and met her husband. She left Szczecin for Israel with her parents in 1949.

At first, Sara lived with her husband and daughter in a kibbutz, then elsewhere. Sara’s husband worked for the Ministry of Defence, and she started working there too in 1956. She went on a diplomatic mission to Poland with her husband and children in 1959, working with her spouse at the Israeli embassy in Warsaw for three years. After returning to Israel, she continued to work for the Ministry of Defence, taking care, among other things, of Jews arriving from the USSR. She retired in 1980 but collaborated with the ministry for another fifteen years. She remained in contact with Poland, translating from Hebrew into Polish and vice versa, as well as from Russian. She published her memoirs, One More Story and Small Stories, which were also published in Poland. She died in 2015.

The Wannsee Conference Protocol

The protocol of the meeting on 20 January 1942 starts with a list of the participants.

In general, the protocol’s language is deliberately designed to largely obscure the extent of injustice and violence. Mass killings planned and already carried out may well have been addressed, but any references to them in the protocol can only be found between the lines.

Section II describes the opening of the meeting. Reinhard Heydrich began by stating his remit and responsibility and the meeting’s aims. Then he continued with a report on the forced displacement of Jews so far. Section II of the protocol ends on page 5. It concludes by pointing out that the previous practice of emigration was now forbidden.

Section III opens by stating that the future approach will be the ‘evacuation of the Jews to the East’. It continues: ‘However, these operations should be regarded only as provisional options, though they are already supplying practical experience of vital importance in view of the coming «final solution of the Jewish question»’. Since the text here also mentions the ‘appropriate prior authorization by the Führer’, it contains a concrete reference to Hitler and his approval of these actions.

On page 7 at the bottom, the protocol deals with the plan of doing more than just exploiting the forced labour of Jews deported to the East: ‘In large labour columns, separated by sex, the Jews capable of working will be dispatched to these regions to build roads. In the process, a large portion will undoubtedly drop out through natural reduction’. In other words, the people were killed through forced labour.

Section IV (the last one) starts with page 10, documents the attempt to establish clear rules on which people should be deported. The protocol elaborates the various relationships in a family, including the so-called first- and second-degree Mischlinge – persons with Christian and Jewish parents or grandparents – as well as the question of ‘mixed marriages’.

There were 30 copies of the Wannsee protocol, but as yet only one single copy had been found. This original of the protocol is at the ‘Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amtes, Berlin’ (R 100857, Bl. 166–188).

Das Wannsee-Protokoll in der Originalfassung

The Wannsee-Protocol in English

The Wannsee Conference

The 15 participants at the meeting at Wannsee were among the Third Reich’s functionary elite. These men helped to organise the mass murders across Europe. Some months before, Hitler had authorised the mass murders which had already taken place at many locations. But neither Hitler nor any of the other top-ranking Nazi leaders were present at the meeting in Wannsee on 20 January 1942.

The only question addressed was ‘how’ to organise the mass murders – in other words, what was the most efficient way to murder millions of people. Reinhard Heydrich asserted his claim to head the organisation and his responsibility for the operation. Heydrich’s leadership role derived from an order issued by Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring instructing him to prepare everything necessary for a ‘total solution of the Jewish question’.

The SS and police organizations were constantly wrangling over competencies with other authorities represented at the meeting over the extent of their powers – for example, with other departments in the Ministry of the Interior or the civil administration of the occupied eastern territories. The main concern of the participants was to safeguard the interests of their own institutions and ensure there was a clear legal definition of who was to be deported.The Wannsee Conference

On 20 January 1942, this villa was the venue for a meeting of 15 high-ranking representatives of the Nazi regime – party functionaries and representatives of the ministries, as well as SS and police officials.

As announced in the letter of invitation, the meeting was to discuss the ‘final solution of the Jewish question’ – a phrase that meant the systematic murder of all Jews in Europe.

The meeting was convened by Reinhard Heydrich, Head of the Security Police and the Security Service of the SS. Heydrich asserted his claim to head the organisation and his responsibility for the operation. Heydrich’s leadership role derived from an order issued by Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring instructing him to prepare everything necessary for a ‘total solution of the Jewish question’. But neither Hitler nor any of the other top-ranking Nazi leaders were present at the meeting in Wannsee.

The only question addressed was ‘how’ to organise the mass murders – in other words, what was the most efficient way to murder millions of people. This act of mass murder had already been authorised on the highest levels of the regime and was already happening in eastern Poland, Serbia and the occupied territories of the Soviet Union.

The SS and police organizations were constantly wrangling over competencies with other authorities represented at the meeting over the extent of their powers – for example, with other departments in the Ministry of the Interior or the civil administration of the occupied eastern territories. The main concern of the participants was to safeguard the interests of their own institutions and ensure there was a clear legal definition of who was to be deported. This meeting later was called the Wannsee Conference.

The Meeting at Wannsee and the murder of the European Jews – exhibition in The House of the Wannsee Conference

The Wanssee Conference

Ewa Hartwig-Fijałkowska’s Collection

In November 2004, the ‘Grodzka Gate – NN Theatre’ Centre received part of Edward Hartwig’s photographic legacy. The photos were handed over in a ceremony during which one of the alleyways in the Old Town was named Hartwigs’ Alley. In the presence of Edward Hartwig’s family members, including poet Julia Hartwig, his Lublin photographs were donated to the Centre by his daughter Ewa Hartwig-Fijałkowska. In October 2014, she donated another part of her father’s photographic archive. And yet another batch of photographs reached the ‘Grodzka Gate – NN Theatre’ Centre in 2016. Thus, a total of 3,339 photographs by Edward Hartwig were donated to the Centre. The last components of Edward Hartwig’s Lublin archive were donated to the ‘Grodzka Gate – NN Theatre’ Centre in 2022.

Edward Hartwig’s legacy, donated by Ewa Hartwig-Fijałkowska, makes up a separate collection of the Hartwig Archive. In addition to photographs by Edward Hartwig, the deposit also contains the Archive of Julia Hartwig and Artur Międzyrzecki.

Symcha Wajs’s Collection

The collection of photographs donated to the ‘Grodzka Gate – NN Theatre’ Centre by Symcha Wajs, a social activist, member of the Board of the Warsaw Jewish Religious Community and an irreplaceable activist in the field of the history of Lublin Jews, is priceless testimony to the Holocaust. These images depict various stages of the Shoah in Lublin, from the establishment of the Lublin Ghetto to its liquidation on 16 March 1942, which marked the beginning of ‘Operation Reinhard’, one of the greatest crimes in European history, aimed at the extermination of the Jewish population of the General Government, and expanded to other German-occupied European countries.

Symcha Wajs’s Collection